Programming with R

Analyzing multiple data sets

Learning Objectives

- Explain what a

forloop does. - Correctly write

forloops to repeat simple calculations. - Trace changes to a loop variable as the loop runs.

- Trace changes to other variables as they are updated by a

forloop. - Use a function to get a list of filenames that match a simple pattern.

- Use a

forloop to process multiple files.

We have created a function called calcGDP that calculates the Gross Domestic Product:

calcGDP <- function(dat, year=NULL, country=NULL) {

if(!is.null(year)){

dat <- dat[dat$year %in% year, ]

}

if(!is.null(country))

{

dat <- dat[dat$country %in% country,]

}

gdp <- dat$pop * dat$gdpPercap

new <- cbind(dat, gdp=gdp)

return(new)

}

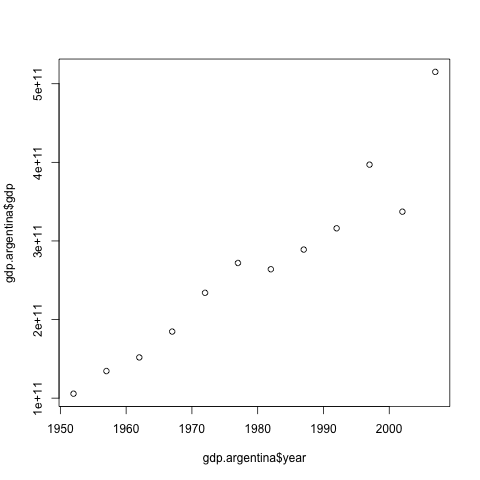

gdp.argentina <- calcGDP(dat=gapminder, country="Argentina")Following the plot example in lesson 05 we can plot the gross domestic product of Argentina over the years:

plot(gdp.argentina$year, gdp.argentina$gdp)

but we have data for 142 countries in our dataset. We want to create plots for all of them with a single statement. To do that, we’ll have to teach the computer how to repeat things.

For Loops

Suppose we want to print each word in a sentence. One way is to use six print statements:

best_practice <- c("Let", "the", "computer", "do", "the", "work")

print_words <- function(sentence) {

print(sentence[1])

print(sentence[2])

print(sentence[3])

print(sentence[4])

print(sentence[5])

print(sentence[6])

}

print_words(best_practice)[1] "Let"

[1] "the"

[1] "computer"

[1] "do"

[1] "the"

[1] "work"

but that’s a bad approach for two reasons:

It doesn’t scale: if we want to print the elements in a vector that’s hundreds long, we’d be better off just typing them in.

It’s fragile: if we give it a longer vector, it only prints part of the data, and if we give it a shorter input, it returns

NAvalues because we’re asking for elements that don’t exist!

best_practice[-6][1] "Let" "the" "computer" "do" "the"

print_words(best_practice[-6])[1] "Let"

[1] "the"

[1] "computer"

[1] "do"

[1] "the"

[1] NA

Here’s a better approach:

print_words <- function(sentence) {

for (word in sentence) {

print(word)

}

}

print_words(best_practice)[1] "Let"

[1] "the"

[1] "computer"

[1] "do"

[1] "the"

[1] "work"

This is shorter—certainly shorter than something that prints every character in a hundred-letter string—and more robust as well:

print_words(best_practice[-6])[1] "Let"

[1] "the"

[1] "computer"

[1] "do"

[1] "the"

The improved version of print_words uses a for loop to repeat an operation—in this case, printing—once for each thing in a collection. The general form of a loop is:

for (variable in collection) {

do things with variable

}We can name the loop variable anything we like (with a few restrictions, e.g. the name of the variable cannot start with a digit). in is part of the for syntax. Note that the body of the loop is enclosed in curly braces { }. For a single-line loop body, as here, the braces aren’t needed, but it is good practice to include them as we did.

Here’s another loop that repeatedly updates a variable:

len <- 0

vowels <- c("a", "e", "i", "o", "u")

for (v in vowels) {

len <- len + 1

}

# Number of vowels

len[1] 5

It’s worth tracing the execution of this little program step by step. Since there are five elements in the vector vowels, the statement inside the loop will be executed five times. The first time around, len is zero (the value assigned to it on line 1) and v is "a". The statement adds 1 to the old value of len, producing 1, and updates len to refer to that new value. The next time around, v is "e" and len is 1, so len is updated to be 2. After three more updates, len is 5; since there is nothing left in the vector vowels for R to process, the loop finishes.

Note that a loop variable is just a variable that’s being used to record progress in a loop. It still exists after the loop is over, and we can re-use variables previously defined as loop variables as well:

letter <- "z"

for (letter in c("a", "b", "c")) {

print(letter)

}[1] "a"

[1] "b"

[1] "c"

# after the loop, letter is

letter[1] "c"

Note also that finding the length of a vector is such a common operation that R actually has a built-in function to do it called length:

length(vowels)[1] 5

length is much faster than any R function we could write ourselves, and much easier to read than a two-line loop; it will also give us the length of many other things that we haven’t met yet, so we should always use it when we can (see this lesson to learn more about the different ways to store data in R).

Challenge - Using loops

- Write a function called

totalthat calculates the sum of the values in a vector. (R has a built-in function calledsumthat does this for you. Please don’t use it for this exercise.)

ex_vec <- c(4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42)

total(ex_vec)[1] 108

Generating Multiple Plots

We now have almost everything we need to generate the gdp plots for all countries. The only thing missing is creating a vector that contains all the countries in our dataset. Using the function unique on the country column of gapminder object, we can extract the 142 countries:

countries <- unique(gapminder$country)

length(countries)

tail(countries, n=3)[1] 142

[1] "Yemen Rep." "Zambia" "Zimbabwe"

Challenge - Using loops to generate multiple plots

Our goal is to generate a script (please go back to your data_analysis R script) that analyses our gapminder data as follows:

Reads the data into a data frame.

For each country the script generates three plots; one of the total population, one of life expectancy and one of gross domestic product over the years.

Save the script and commit the changes.